Minnie and The Moonrakers I Electronic Press Kit

Minnie and The Moonrakers I

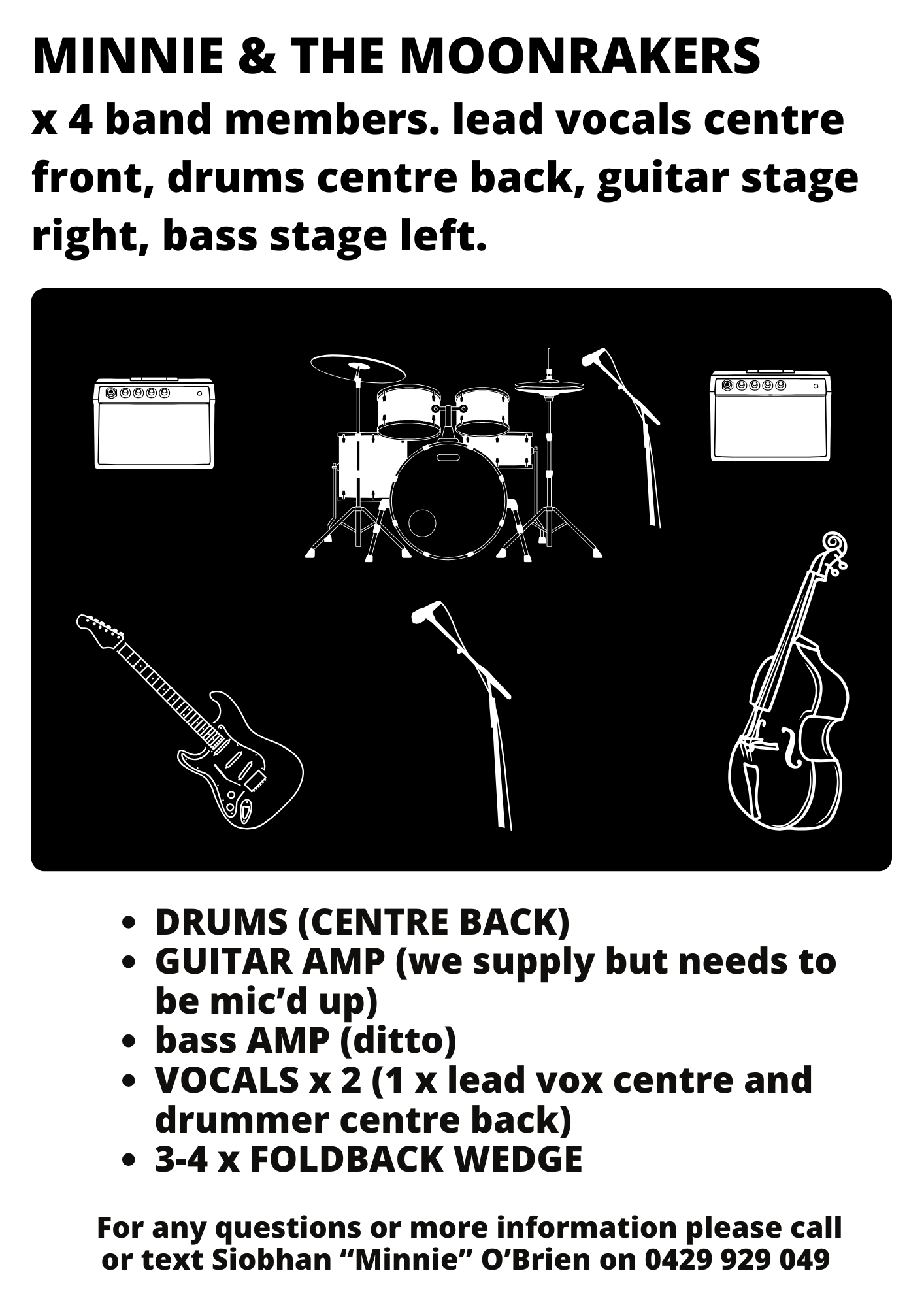

Tech Specs

Minnie and The Moonrakers I

Official Artist Images

Minnie and The Moonrakers I

Official Artist Images

Minnie and The Moonrakers I

Official Artist Images

BLOG

Moving Tale Shines Light on Trauma

In a country at war, what happens to the people when the gunfire stops? Siobhan O'Brien explores the hidden costs of conflict in her historical fiction novel. (syndicated across NewsCorp publications nationally)

The term post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – now a household name – wasn’t around during the Great War. Back then, the psychiatric condition that stems from the experience of severe trauma or a life-threatening event, was referred to as shell shock, soldier’s heart or war neurosis.

It wasn’t until 1980 that the expression PTSD was coined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association. However, knowledge of it has been in existence since the world’s earliest conflicts. The first case of it was reported in the account of the battle of Marathon by Herodotus. It was written in 440BC.

The psychological impact of war is one of the theme’s in my recently published novel All the Golden Light. The book isn’t set in a warzone, it is based in a fictional town on the south coast of New South Wales in the final months of the World War I (WWI). It explores what happened to the soldiers when the guns stopped, returning home to Australia with the sound of shells still ringing in their ears. How did these men deal – or not deal - with their internal scars? What impact did peacetime and a new normality have upon those who welcomed them back?

Many novels and screenplay’s set the denoument at the end of the war. Birdsong. All Quiet on the Western Front. A Long Long Way. In All the Golden Light I did the reverse. Why? Because I wondered: We had peace again. But did we really?

For newcomers, here’s a speed date style precis of the book: Adelaide Roberts accompanies her father to a nearby island to deliver much-needed supplies. While loss and deprivation has decimated the country, Adelaide is determined to live a life of purpose and hope, and dreams of living an independent life. On the rocky outcrop she meets lighthouse keeper Emmett Huxley, an outsider haunted by his service in France, taking refuge from the damage of the war. Adelaide and Emmett are drawn together, but plans have been made for Adelaide and the decorated returned soldier Donal Blaxland, a local land-owner with a large tobacco plantation. Soon Adelaide is forced to make a choice about her future, and discovers that Donal harbours terrible secrets of his own.

The seeds for my novel germinated long ago. My maternal grandfather was a raconteur who fought in World War II (WWII), recited Banjo Patterson’s The Man From Snowy River by rote on his 80th birthday and lived to 101 years. I grew up with Pop telling stories about his war years spent in Papua New Guinea, the privation he and his family endured as a child, and the time, many years later, when he and Nan took returned soldiers into their home to care for them. As a young girl I didn’t know how to verbalise these things but I palpably felt the events were there in the room and they became part of me.

Fast forward a few decades and I witnessed my father unravel from emotional and financial tragedy. He was an avoidant who learned from an early age that inner wounds weren’t spoken about or acknowledged. People from his era – the returned soldiers included - were expected to get on with things. He became angry, bitter and turned to addiction to try to ease his pain which became like a blocking point in his brain and psyche. Now he is no longer here to change the narrative.

The impact that this has upon those within the sufferer’s orbit has far reaching consequences. Enter Ada stage left. Even though she, her father and their community live in a seemingly remote location on the other side of the world far from the battlefield, they can’t avoid becoming entangled in the effects of it. Adelaide witnesses the impact of trauma on a daily basis in the convalescing home where she works, grapples with it because her brother has had a catastrophic injury that’s left him paralysed and experiences the hardship that the war has on day-to-day life.

Then she meets Emmett and Donal who return from the warzone with differing ways to deal with what they’d seen and done. But in the early 1900s there was no proper treatment for what they had. The flashbacks, nightmares and hypervigilance. These men, and countless others like them, were indelibly changed. They couldn’t recapture what they’d left or undo what they had witnessed. And the loved ones who awaited their homecoming were unable to understand the atrocities they’d endured, much less soften the blow.

The Great War was not the war to end all wars as was said at the time. There have been innumerable conflicts since - too many of them to list here- and now we are grappling with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the horrors in Gaza. But WWI sets itself apart as it was unprecedented in scale. It was the first war to be fought on land, at sea and in the air. And it has the dubious distinction of being the first modern war with modern destructive weapons.

110 years. That’s how long it’s been since the end of the Great War. 2024 and 1918. They seem like two different galaxies. But there is a link. We are human beings who suffer the scars and trauma of human existence.

aboutregional and regionillawarra focus on news, views and community events in the Illawarra (centering on Wollongong) and the Capital region (Goulburn, South East NSW, South West Slopes and Snowy Mountains). Read some of my stories…

recent editorial…

Read an excerpt of All the Golden Light I Chapter One I Belowla, 1918

I

Read an excerpt of All the Golden Light I Chapter One I Belowla, 1918 I

Twenty-three-year-old Adelaide Roberts’ stiff skirt crackled. Sweat trickled down her stomach, and she adjusted her hat to block out the biting sunlight that streamed through the banksias on the edge of the cliff. All around her, dozens of graves were marked with crucifixes that pointed to the sky like tiny ships’ masts. In this cemetery, Ma was everywhere – amid tussocks of grass, on the tongues of fungi, in windswept trees bent as if in prayer. Adelaide couldn’t believe it was two years since she’d passed away.

Da stood beside her, dressed in his best herringbone jacket, moleskins and leather riding boots. He was still handsome, but lately his face had grown weathered and his clothes a little looser. In the broad daylight his eyes were like cuts in his skin as he looked at her, seemingly for answers.

Adelaide didn’t ask what he was thinking. She already knew. He wanted her to find God and contemplate marriage. The Kaiser’s antics on the other side of the world meant her father could no longer afford to keep her. Da made a living operating boats to deliver supplies and selling wool and milk, but the war had drastically reduced the local workforce and, without help, the family farm was failing. The drought in 1914 hadn’t helped much either. Nor had a series of shipping strikes that had reduced her father’s business to peddling to the few locals that could afford what he had to offer.

But the idea of being discarded made her furious. They’d been over it so many times that she’d given up listening. He turned from her, back to his wife’s grave. The grey marble headstone was inscribed with a simple epitaph: Forever in our hearts, Harriet Roberts, 1879–1916. It was a handsome grave, as far as graves went, even though Da hadn’t had enough money to make it as ornate as he’d wanted.

Year by year the war had taken its toll, and Adelaide knew he worried about how much longer he could hold out without selling up. The forty-acre plot where she and her father lived on the periphery of Belowla wasn’t the finest land in the district. It was more suited to sheep than wheat. Da had been bequeathed the property in the formative days of his marriage to Ma by an Uncle Mordue he never knew existed until the day he received a letter from local solicitor and long-time mate Barnaby Sunderland. The land was a boon for the young married couple but was only ever considered a place to raise Adelaide and her brother Joseph, ten years her senior – until the effect of the war on the economy forced Da to think otherwise.

Da’s father had always joked that his son must have been pickled in brine, he loved the sea that much. But the jibe didn’t last after Ned left school at fourteen to work on the wharves and secured his first boat a year later. By the time the new century arrived, he’d added a dozen steamers to his fleet that ferried butter, mail and coal to places with names that danced off the tongue, such as Moruya, Narooma and Wagonga. Customers from Sydney to Eden endorsed his timely supply of goods, passengers and livestock, but bemoaned the indelible stench of the pigs.

A teenaged Adelaide grew accustomed to the odour as she and Joseph piloted her steamer of preference, Cobargo, up and down the coastline catching gurnard, picnicking on remote outcrops and finessing their navigational skills. Ned encouraged his children to borrow his boats. He relished the idea that they’d learn how to use them, gain a respect for the ocean and perhaps fall in love with the vessels too. But it was on the proviso that they only used them on his days off. Sergeant Wallace Greensborough’s son, Patrick, invariably joined Adelaide and Joseph, and the trio often returned home flushed like freshly boiled prawns.

These pursuits were brought to an abrupt halt shortly before Adelaide’s sixteenth birthday, when Ma deemed them unladylike, especially as Patrick, like Joseph, was a decade older than Harriet’s precious only daughter.

Joseph believed that peace was forged through words, not fists, but when the war broke out his parents convinced him he had no choice but to enlist. Reluctantly, he marched from Nowra to Sydney in an ever-growing column of khaki-clad young men, before sailing onward to France. The Waratah March they called it. Adelaide often reflected upon how difficult it must have been for Joseph to assimilate in the army given his views.

Ma passed away not long after that. Food prices went up, employment went down. Recognising there was a demand for wool and milk, Da sold most of his boats and bought a flock of sheep and a small herd of cows.

Honour boards listing the names of those who’d gone to the war were put up in public buildings in every town across Australia. Adelaide’s best friend, Gwynne Sunderland, daughter of the solicitor Barnaby, told her she’d spied Joseph’s name on one of these lists. Adelaide couldn’t bear to look at it, and the thought of doing so roused a sense of shame within her that she hadn’t done more to help her brother avoid the atrocities. In her imagination the letters on the noticeboard glowed with a spectral incandescence, even at night.

When she and Da had arrived at the cemetery, Adelaide had filled the vases on Ma’s grave with a mass of gardenias – the aroma danced in her nostrils now.

‘Hail, Mary, full of grace,’ Da said, his hands clasped in prayer.

Adelaide had recited this prayer so many times, but she’d never comprehended its meaning. ‘Blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus’ made no sense to her. Nor did a virgin birth or an imaginary deity in the sky. There were many things she failed to grasp now that Ma had passed. She frequently wondered how seemingly astute individuals such as her parents could send their only son to the war despite his resistance, and maintain it was a Catholic’s duty.

‘Sacrifice is a divine blessing, Ada,’ her father would say when she voiced her feelings. ‘Want a white feather? Ask a Protestant.’

Now Joseph was living in Birmingham, England, after being paralysed by a shrapnel wound to his spine. Having relocated there with Jocelyn Moncrieff, a nurse who’d cared for him in Calais before he’d recovered sufficiently to marry her, he’d vowed never to return to Belowla while either his mother or father were alive.

Why hadn’t Adelaide intervened, opposed her parents and done more to help Joseph? It pained her to think how her life might have transpired if she had. Now Da sought to offload her, and the only one who’d understand her resistance to that was Joseph.

Her mind returned to Ma and it dawned on Adelaide that hard on the heels of death comes the realisation that unspent love has nowhere to go. Perhaps that was the embodiment of grief? Love without a home.

At her mother’s funeral, she’d stood beside the casket in the church, tormented by guilt and shame. It was her fault her mother was dead. There was no one else to blame. Whichever way Adelaide mulled it over, as she’d done countless times since the accident, her part in Ma’s death was irrefutable, a fact. While the congregation sang about the Almighty Father, Ma had looked as if she was asleep, lying there in her pale lilac dress, a little rouge showing on her alabaster cheeks. Adelaide had felt the congregation’s eyes upon her. If she could have, she would have run from the church, back through time, and stopped the tragedy from occurring. She’d have put Ma on a different horse, taken her along a different track, and then Ma would still be with her.

Birdsong brought her back to the present and she shook herself. Da glanced at her and she mouthed the prayer wordlessly with him: ‘Pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death.’

Adelaide adjusted the bodice of her hospital uniform and brushed back a stumpy coil of hair under her hat. She’d hacked her long, blonde tresses with dressmaking scissors after Ma died, and now was waiting impatiently for them to return to their former abundance. She scrutinised her father and found no trace of the man who had once loved her mother, only a stern countenance and a faint whiff of grog. She loved Da and knew he loved her, but they were like two points of a compass – one pointing north, the other south.

Da made the sign of the cross and wheezed heavily, his lungs scarred by tuberculosis.

‘Whose death are we praying for?’ Adelaide asked. ‘Ma’s or our own?’ She shocked herself. She’d always thought these things but never said them.

Da sighed and met her gaze. His eyes were dark, impenetrable.

‘Certain sentiments are beyond mortal knowing. God has a plan … for us all, Ada.’

‘I’m not here for a divinity lesson.’ She bit her tongue. What on earth prompted her to say such things? To speak to Da like that. She’d always tried her best to please him. She went to church, cleaned the house, cooked the meals, worked at the hospital to care for injured soldiers. In many respects, she’d become the wife he’d lost.

‘Hush!’ His eyes darted about as if he expected someone or something to appear from behind a tree. The waves hurled themselves at the rocks.

Adelaide winced as he took hold of her wrist and led her towards the cemetery’s front gate. It was as if he didn’t want his dead wife to hear. Adelaide stumbled blindly behind him, thinking of the tin of money stashed under the floorboards of her bedroom, earned from the dresses she’d sewn for the women of Belowla in the little time she had spare. When this cursed war was over, she’d find her brother and his wife wherever they were in the world, and together the siblings would set up a dressmaker’s in Sydney, just as they’d always planned, though she knew it would break Da’s heart. Bespoke garments and fine fabrics would line the shelves, a brass bell above the front door tinkling whenever a customer came or went. Women – unemployed, unmarried or widowed – would come from distant corners of the state to learn the skills required to design, make and sell clothes.

She’d got the idea from an article in The Argus newspaper about a female labour colony initiated by feminists Vida Goldstein and Adela Pankhurst, in Mordialloc, Victoria. Joseph was enraptured by the plan when his sister had put it to him. He was a rare individual with the capacity to embrace expansive notions and alternate perspectives. Adelaide was yet to unearth such a combination in another man, and she ached for Joseph’s return. Yet she was aware the brother she had known might no longer exist, was probably just a memory, a shadowy wraith who inhabited her thoughts and plagued her dreams, and she was uncertain who would arrive in his stead. She wondered whether Da ever thought about his son or even cared about the fact that he would never walk again. Joseph was dead to him – and had been to Ma when she was alive – because of his opposition to fight in a war that he said had nothing to do with him or Australia.

Adelaide looked past her father at the dust that swirled along the road to town. The local show had started and he was anxious to be there for the horse race. She hung back; she couldn’t bear to have the same conversation about finding God and a suitable husband again. In between a horn honking and the noise from a vehicle driving by, she heard ‘settle down’, ‘marriage’, ‘partner’. It was the discussion she’d been anticipating all day. But her mind was on the car that abruptly came to a stop beside her.

Gwynne Sunderland swung down from the front seat. She looked smart in her white uniform with a red cross emblazoned across her bust. ‘It’d be easier to find the prime minister,’ she said, smoothing the creases in her skirt and winking at Adelaide. ‘The matron wants us at work earlier than usual this afternoon.’

‘Certainly,’ Adelaide said and cast a surreptitious look at Da. ‘But not before we go to the show. Can you take us?’

ARTIST IN RESIDENCE

Creative central

Writing, making music and squeezing as much joy as possible into every single day are the keys to fulfillment according to author Siobhan O’Brien.

By Kirsty McKenzie

Australian Country Magazine

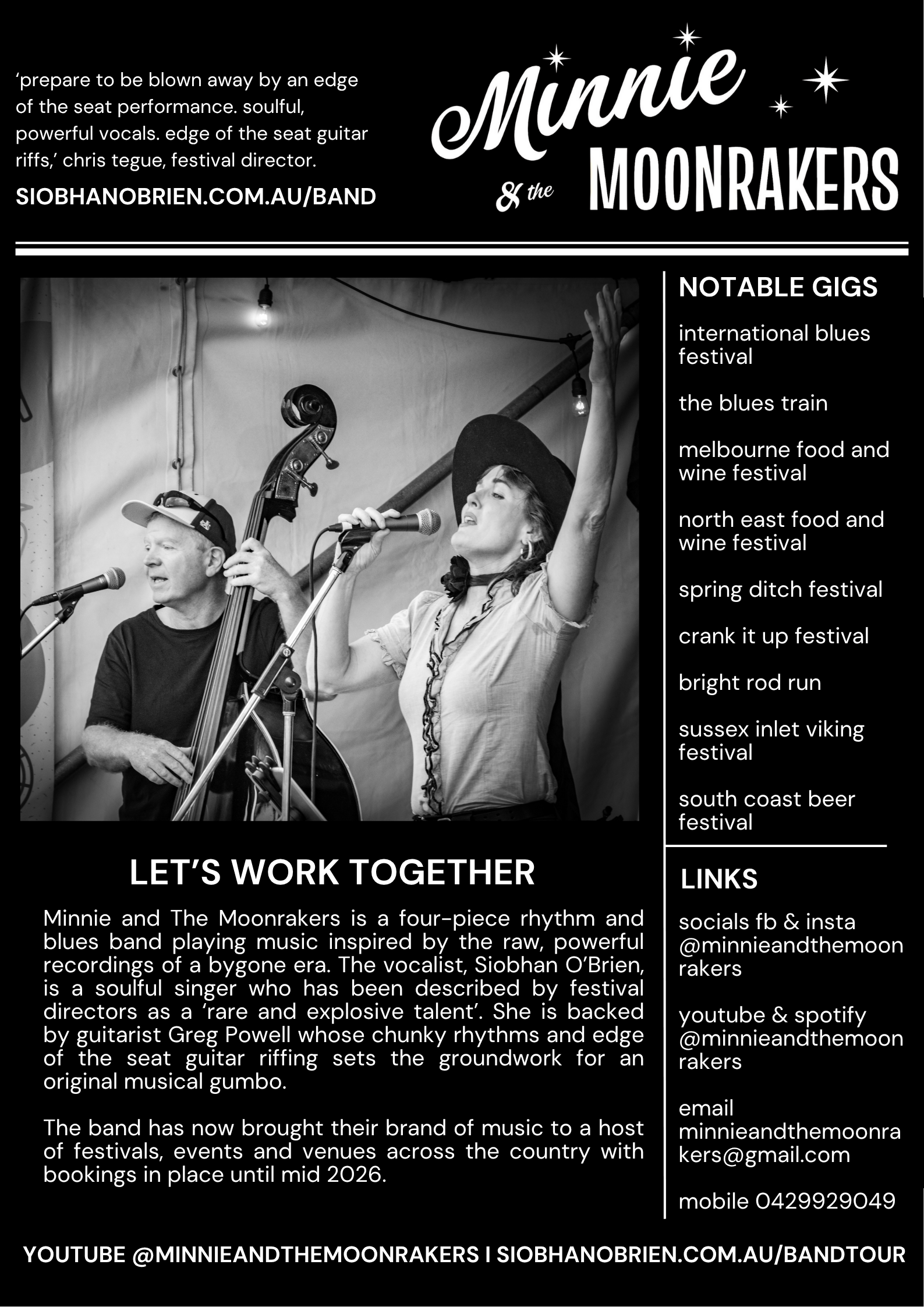

While most people would have found home schooling three teenagers enough of a challenge during the COVID lockdowns, journalist and author Siobhan O’Brien felt the need to stretch herself just a little bit further. First, she and her husband, accomplished wine writer, chef and accommodation manager Greg Duncan Powell took up online yoga in one of the empty guest cottages he was managing at Bawley Point on the NSW South Coast. Then Siobhan decided it was time to learn to sing, so found a teacher and embarked on a year’s lessons via Zoom. In 2021, she celebrated her new-found skills by forming blues and roots band Minnie and The Moonrakers and reinventing herself as the lead singer with Greg on guitar along with a drummer and double bass player. What began as a passion project has taken off and Siobhan, her alter ego Minnie, and the band are now performing four to six gigs a month.

In her ‘spare’ time, Siobhan has been working on her first novel, All the Golden Light, which was launched in March. The book is a rollicking read set in the Shoalhaven region, where Siobhan and Greg have spent much of their adult lives. It begins at the end of WWI and Siobhan’s protagonist – a fiercely independent nurse – is dealing with traumatised soldiers returning from the battlefields. She’s also defying the conventions of the time by sewing in the evenings to fulfil her dream of escaping to Sydney to start her own dressmaking business.

Siobhan says the book was a long time in the ferment, as she had dreamt of writing it for years and has numerous less successful manuscripts stashed in her bottom drawer. On the advice of a friend in the publishing industry, she was determined to make her first shot her best and embarked on several courses through the Sydney Writers’ Studio in the lead up to hitting the keyboard.

“I did two novel and screen writing courses over a couple of years,” she explains. “It was an imperative as writing a novel is a very different skill set to journalism. It’s all about the architecture upon which you hang your story and the mechanics of constructing the novel with the character arcs and turning points in the narrative. Sometimes it felt counter-intuitive to the creative process, but I would never have finished it if I hadn’t gone through the learning process.”

In fact, Siobhan has been finding outlets for an abundance of creative energy all her life. Her parents hoped to channel her relentless drive by sending her to a French-speaking school in Canberra. When they moved to Batemans Bay during her final school years, she was sent to boarding school in Ballarat. She candidly confesses she was “a bit of a handful” and at one stage was suspended for sneaking out at night to listen to bands and stealing the number plate from the head nun’s car.

After travelling for a year, she found her metier when she was accepted into a communications course at Charles Sturt University in Bathurst and subsequently moved to Sydney for a marketing role in a finance company. “I spent most of my time writing poetry instead of doing my real job,” she says. “Fortunately, I found journalism or journalism found me when I started sending travel stories to The Sydney Morning Herald.”

From there, Siobhan moved into writing about property and interior design and went on to become editor-in-chief of Indesign magazine. In the early 2000s she wrote several design books, including A Life by Design, a biography about socialite wallpaper designer Florence Broadhurst. By 2003, she and Greg had moved to the South Coast where they both continued writing and Greg managed Bundle Hill Cottages.

In a novel-worthy twist, it was during a weekend away with her mother at one of those cottages that she and Greg first met. “I was 23 and it was a meeting of the minds,” she says. “He’d done an honours degree in in medieval French history and I had studied French for all those years. We were both writers, so there was an inevitable spark. We were together for about 18 months and then I choofed off with my career in Sydney. But I always kept tabs on him through mutual contacts and he came back into my life a few years later.”

Long-time readers may recall Australian Country ran a story about Siobhan and Greg more than a decade ago when the children, Evie, now 20, Earl, 19 and Beatrice, 16, were youngsters and the family was living in a hillside home with stunning views to the ocean they’d built beside the cottages. At that time, Siobhan discussed how initially she commuted between Sydney and the bush but, as the children came along, she took the leap and moved permanently to Bawley Point.

“The South Coast is very beautiful but there are no really great jobs and it became apparent quite quickly that if I wanted opportunities, I would have to create them for myself,” she recalled at the time. “It was completely overwhelming at first but soon I got a regular freelance work and then an offer to write a book, so I said ‘yes’ to both and got busy. There was a lot of breastfeeding at publishers’ meetings and, before I knew it, I was up to book four. Greg was also working on a cookbook and we were extending our house, so we were living in one of the holiday cottages. Greg was doing as much of the work on the house as possible to save money and, frankly, it was a nightmare. Somewhere along the line after Beatrice was born I just realised it wasn’t working for me. I had this feeling that I was giving away the power to control my future and finances and, as a responsible mother of three young children, I wasn’t comfortable with that.”

At night, when the babies and books and articles had finally been put to bed, Siobhan started exploring other aspects of her creativity. She looked to her passions for art and design and started painting, a jewellery-making course, screen printing and sewing. The kitchen benches strewn with beads, fabric swatches and sketchbooks filled with fashion designs distilled into Miss Moss, a fashion label and an associated shop in Milton.

After 14 years in the business, Siobhan reached the stage where it became more of a chore than a creative outlet. “I was over it,” she says. “I realised that the main motivation for the shop had become earning a living. Selling footwear, it seemed every second customer wanted to show me their bunions and I’d had enough. So I closed the shop and that freed me up to concentrate on writing.”

Meanwhile, there were more challenges in the form of the Black Summer bushfires of 2019/2020, when their home and cottages were surrounded by fire and sustained significant damage. “It was a case of life imitating art as I’d already written a bushfire into my book,” Siobhan says. “There was nothing esoteric about it as when you live so closely with nature inevitably there will be fires.”

When lockdown started in March of 2020, Siobhan barely had time to process the trauma and channelled her anxieties into singing and writing. Post-lockdown, the reminders of the fires all around them grew too much and family moved to their present home, with yet another stunning view, this time overlooking Burrill Lake. At press time, they are on the move again, heading to Bright in Victoria’s north-east.

“The band has been really well received there,” she says. “We’ll continue to tour and perform in NSW, just with closer access to the mountains and all that the region has to offer. We’re keen skiers and cyclists, so we’re looking forward to the move. Performing is so life affirming. Greg has always been in bands and I never fully understood how much he got out of it. But now I do. I’m never scared to go on stage. I have no nerves or apprehension. I feel excited but having lived through the fires, I think I have a bit of an attitude of ‘what’s the worst that can happen?’ I’m also working on another book and it feels like the time is right. We can finally take the time to pursue the things we love and really focus on following the creative urge.”

All the Golden Light.The Journey.

Some years ago I decided to write the novel I’d been dreaming about since my early twenties. I’d had other books published – A Life by Design - a biography that explores the life and times of Sydney socialite, wallpaper designer and not entirely likeable charlatan - Florence Broadhurst who was murdered in 1977. The crime remains unsolved and my book was the first biography published on the subject matter. Broadhurst is now internationally recognised.

On the heels of this book came Hello Darling: The Jeanne Little Story (Allen & Unwin) that shackled me with the memory of dropping my toddlers Evelyn and Earl (now young adults) at preschool with Jeanne perched – at her own insistence – in the baby seat. I still recall the bemused faces of the other young mothers upon our arrival.

Not long thereafter I gave birth to my daughter Beatrice and writing was off the table for me for a while. But the creative itch to write a novel remained. In the years that ensued I mucked around with a few ideas, broaching them with my literary agent Benython Oldfield who swiftly set me straight - “Write it. Call me when you're done.”

Fast forward a few years the hefty manuscript of some 130,000 words found a home with HarperCollins (Australia). Now All the Golden Light is a richly themed historical story set in 1918 on the remote south coast of New South Wales and tells the story of Adelaide Roberts as she fights for love and self determination during the last gasp of World War One. Accompanying her father to a rugged island off the coast, Adelaide meets the enigmatic resident lighthouse keeper Emmett Huxley, an outsider taking refuge from the damage of the war. They are inexorably drawn to each other, but Adelaide’s future has been mapped out already, marriage to the decorated soldier Donal Blaxland, a man with his own dark secrets. Torn between love and loyalty to the two men, Adelaide finds herself caught in the damage that the trauma of war has enacted upon them both. Between the rocky outcrops of the island, the wild ocean and the bush of an ancient land, Adelaide must fight for her survival, determined to live and love on her own terms. It is a dramatic novel about finding connection, meaning and beauty in a time of darkness … and the craving and savagery of the heart.